This post has been a long time coming.

But first, some lyrics:

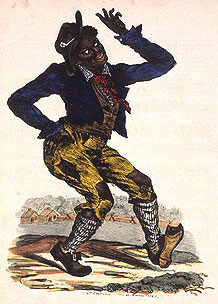

Wheel about, an’ turn about, an’ do jis so;

Eb’ry time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow.

— Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice, Jump Jim Crow

While Lewis Hallam is believed by some to be the first white comedian to perform in blackface (that was in 1789), and Robert Toll in Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America suggests it was Charles Matthews, it is Thomas Dartmouth Rice who is often acknowledged as the “father of American minstrelsy” — the first white stage performer to wear blackface makeup (at the time, burnt cork applied to the skin to darken it) and successfully perform as a black man. That was around 1828. He is most often associated with the phrase Jim Crow, a circa 1828 caricature of a crippled plantation slave, singing and dancing.

(I fully realize asking the obvious question — why not just get a black actor to play the part of a black man? — short-circuits the long, circuitous route I enjoy so much taking in making whatever point I have in mind in these blog posts, so why not let’s just forget I brought it up.)

Although closely identified with whites masquerading as blacks, minstrelsy was also later performed by black actors, too.

From the Wikipedia entry:

Minstrel shows portrayed and lampooned blacks in stereotypical and often disparaging ways: as ignorant, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, joyous, and musical. The minstrel show began with brief burlesques and comic entr’actes in the early 1830s and emerged as a full-fledged form in the next decade.

Minstrelsy presented a version of black people that was based on exaggerated stereotypes. White actors playing the part of black people doing the sorts of things no one was actually doing. If there was anything to make it worse, its when black actors played the part of white actors playing the part of black actors doing things no one actually did in real life. (How’s that for convoluted?) The wild popularity of minstrel shows contributed to creating some of the racial epithets we carry with us to this very day. Once an idea takes hold, it’s almost impossible to blot out.

Allow me to be blasphemous for a moment: mentalism is a branch — a form — of magic. Now, I know that just irritates the snot out of some people, but it’s a fact hard to get around. Still, mentalism has a fit and form all its own — a face, if you will — that we know when we see it.

There is a growing contingent in the mystery entertainment world that suggests much of what passes for “mentalists” and/or “mentalism” is, for all intents and purposes, nothing more than magicians masquerading as real mentalists. And, I detect, the problem is not so much the lowly magician encroaching as it is magicians presenting a form of mentalism that is not genuine, real mentalism but, rather, a demeaning caricature.

What is real mentalism? I’ll give you a hint: it doesn’t matter what we think it is, it’s only what audiences think it is. (And they don’t use the word mentalism anyway.)

If, in the world of blues guitar, Clapton is god, then in the world of mentalism, Annemann is god. From one end of the mentalist landscape to the other, Annemann’s work — especially The Jinx — is pointed to as seminal work. Max Maven is reported to consider the writings of Ted Annemann the greatest historical influence on his work. (M-U-M March 1979).

From the innaugural issue of The Jinx, October 1934:

“Conceived, written and published by Theo Annemann, The Jinx is not a magazine, neither is it a crusading sheet with a chip on its shoulder and a woodpile in reserve. All offices, both in an artistic and business sense are held by one individual who has but a single thought in mind, that of supplying magicians and mystery entertainers at large with practical effects and useful knowledge.”

Bob Cassidy points to Henry Hays’ Amateur Magicians Handbook and states it was his “gateway into the world of magic and my first step to mentalism. It would be another five years before I heard of a guy named Corinda.” (Hay’s book is one of Cassidy’s “The Thirty-Nine Steps — A Mentalists Library of Essential Works.”)

Richard Osterlind regularly points to the Tarbell Course in Magic as a rich source of mentalism.

I could go on, but, at this point, I’m either preaching to the choir or talking to a wall.

People like John Edward and Sylvia Browne chap my base because they present a front that I consider an affront. In a very pleasant conversation I had recently with a cyber crime specialist in the Federal Bureau of Investigation, I made note that I consider what people like Edward and Browne do should be criminal. Unfortunately, I can only offer my opinion that their actions are morally and ethical corrupt.

How far between “mental magic” and Edward and Browne are your beliefs? Just asking.

It’s worth noting that Rice, the original Jim Crow, became rich and famous because of his skills as a minstrel. He may have lived “an extravagant lifestyle,” when he died in New York on September 19, 1860, he died in poverty.

One last note: Rice’s brand of entertainment would later be considered a form of racism, although it also opened the door for black performers.

Two things in passing. Cassidy points to the Henry Hay but Hay admits that the majority of his mentalism section is from Annemann and points to Annemann.

Secondly, what did the FBI agent reply regarding Sylvia Browne?

All roads lead to Annemann, don’t they. And Annemann was a professional magician who wrote The Jinx to…wait for it…magicians.

The agent, to no one’s surprise, shared with me no opinion on Browne. I suspect the subject was part of calibrating my opinion with respect to the over all conversation.

That said, I know him to be a good and decent man, so I’ll presume his opinion is in line with what any decent citizen of planet earth would hold for that woman.

Thanks for the visit. (I STILL HAVE A READER!!!)

John